Twenty kilograms of newspaper, four plant presses, hand lenses, measuring tapes, sharpened pencils, printed site maps and anoraks. Not to mention enough vary (rice) to support an energetic team of biologists, local guides, drivers and gendarme (local guards) for two weeks. We were prepared.

We set off from the Kew Madagascar offices in Antananarivo in late February 2025, the tail end of rainy season, with three off road vehicles and high hopes of reaching the so-called Lost Forest of Ivohiboro in the southern reaches of Madagascar’s extensive escarpment. Not for the remarkable humid forests, but rather to sample the surrounding grasslands and savannas around the isolated mountain massif. These surrounding open grassy ecosystems are often described as a desert or barren landscape, justifying targeting these habitats for forest restoration in the form of tree-planting. Yet, these grassland-forest mosaics are typical of Madagascar’s Central Highlands and starkly represent the current conservation narrative in this region: plant trees, restore and protect the unique forest biodiversity and keep the frequent grassland fires at bay.

However, decades of research continue to bring to light the unique nature of these Malagasy grassy ecosystems. They are not barren. Many of the open grassy flora arrived voluntarily on the island millions of years ago, over half of the grass and over a third of the sedge species are endemic, and many fire-adapted forbs and trees are found only in these habitats. Still, much remains unknown. Vast regions of Madagascar’s plants, both light- and shade-loving species, remain under- or un-sampled. So where does this grassland biodiversity sit? What functionally distinct types of grassland-savannas do we find? Where are the most optimal sites for grassland conservation, livestock grazing and tree planting? And how can we best understand and manage the ancient interaction between grasslands, forests and fire?

To help address these questions, we aimed to catalogue the grassland flora surrounding the Ivohiboro humid forest during its peak flowering period. After three days of travel, we arrived at Analavoka, one of the first villages where the massif comes to view and one of the last where one can rest, grab a coffee and mofo gasy (fried bread) and send messages assuring our colleagues and families of a safe trip. However, our plans were halted. Cyclone rains had poured down in the surrounding Andringitra watershed and flooded the Menarahaka river in front of us. We were generously hosted in a local church, biding our time. The deluge continued, bringing trees and branches downriver from the surrounding valleys and making the low-water crossing impassable.

Image 1. The Menarahaka flooding its banks with the Ivohiboro massif peeking out in the distance behind the clouds.

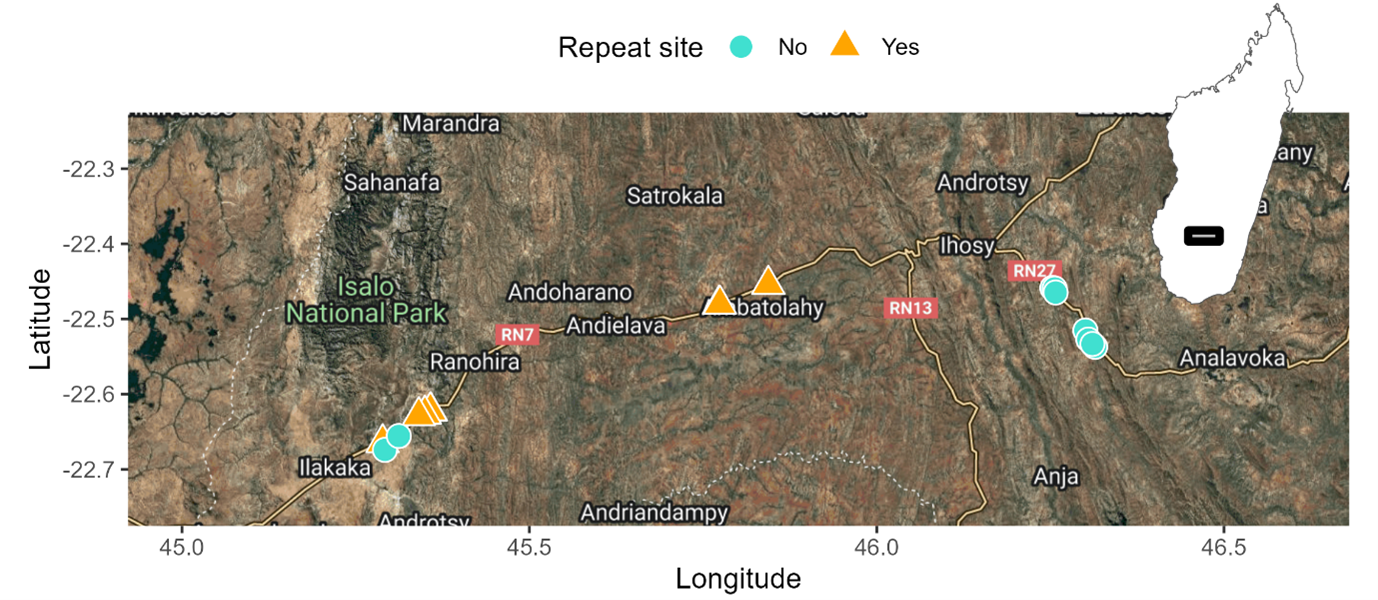

The months of planning would not be put to waste. We quickly changed plans, setting up base in the town of Ihosy. Following the standardised Global Grassy Group (GGG) protocol, we sampled seven grassland sites along the rolling mountain chains in Ivohibe before traversing the extensive Horombe Plateau to the sandstone outcrops of Isalo. Putting our plant presses to good use, we collected 142 new plant vouchers across 17 sites with eight of these sites being re-samples - following the footsteps of previous research visits, completed over 10 years before.

Image 2. The 17 sampled sites across Madagascar’s southern Central Highlands. Starting in the east, we crossed over to Isalo, before completing two repeat sites in Horombe Plateau on our drive back to Antananarivo.

Image 3. Norotiana, Kelda and Lanja organising vouchers, while the sampling team count and collect plants and interact with local guides –sharing our methods, while discussing the species composition and history of grazing and fire in the landscape.

We counted 1,144 individual plants across our sampling plots, finding a range of taxonomic and functional richness across the region. From the tussock-forming Heteropogon contortus-dominated landscapes of Ivohibe, to the forb-, sedge- and geophyte-rich Isalo with endemics like Polygala isaloensis, Distephanus poissonii, localised grasses Panicum palackyanum and Panicum ibitense and terrestrial orchids Habenaria and Cynorkis.

Image 4. Heteropogon contortus, immediately recognisable by its tangled, twisted awns, is one of the dominant grass species sampled across Ihorombe.

Image 5. Habenaria, a terrestrial orchid, found along the rocky pavements of Isalo.

After careful identification of all vouchered specimens, these 17 new GGG datasets will be contributed to the over 550 datasets collected in Madagascar to-date. With this maturing grassland flora catalogue, the TANETI team (Tanety Enti-mikajy Tontolo Iainana, meaning Malagasy Grasslands for Maintaining and Enhancing the Environment) aims to optimise the spatial planning of conservation and restoration outcomes in Madagascar’s mosaic ecosystems - for the betterment of both forests and grasslands. With continued research into their social, ecological and conservation value, we aim to further unearth the importance of Madagascar’s forgotten grasslands and put them on the map for the recognition, integration and conservation of all ecosystems. Though we did not reach Ivohiboro, we aim to return and hope for now that the spillover from our research outputs and local engagement will help shape a more holistic approach to species and ecosystem conservation going forward.

Image 6. The TANETI field team in Isalo. From left to right: Mbola Rakotondratsimba, Edouard Razafimahatokindraibe (Isalo cook), Nantenaina Rakotomalala, Norotiana Rasambo, Jean Augustin Randriamampianina (FOFIFA), Yvon Tovondrainy (Isalo local guide), Lanja Maminirina Rajaonarison, Sedera Ny Aina Ranaivoson, Niaina Randriatsarazaka, Kelda Elliot, Noro Fenitra Harimbao Randrianarimanana. Joseph White was taking the photograph.

Image 7. Mbola, Fenitra, Norotiana, Yvon and Jean Augustin carefully identifying plants inside the 1m-diameter GGG plot in Isalo.

Image 8. The vast grassy plains of the Horombe Plateau, an important region in southern Madagascar for zebu pastoralism.

Image 9. Nantenaina collecting a reference set of grasses at Isalo.

Image 10. The palm savannas and sandstone outcrops of Isalo.

The TANTEI project is funded by the Global Centre for Biodiversity and Climate (GCBC). Find out more here.