Two budding researchers Elaine Slooten and Eulalia Jordaan, from the North West University (NWU) in South Africa embarked on a two-month sampling journey to gather soil and floristic data. This expedition was part of the Future Ecosystems for Africa (FEFA) program for their MSc’s, supported by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation, Frances Siebert (NWU), and Sally Archibald (University of Witwatersrand).

The aim of this research is to determine to which degree the floristic and functional diversity, as well as the carbon stocks (including soil – and plant organic carbon), of Highveld grasslands in South Africa can recover after being ploughed. It highlights the risks of ploughing South Africa’s grassland ecosystems and informs landowners and land-use planners about these risks. Our published paper in the South African Journal of Science summarises international studies, illustrating that biodiverse ‘old-growth grasslands’ can lose up to 50% of their soil carbon during ploughing.

We started our fieldwork in Potchefstroom, enduring the scorching 38°C sun, wasp attacks, and the silent assault of pepper ticks! After a month of intense soil and floristic sampling across 20 plots of 50m x 50m, we packed up and moved North East to Mpumalanga to sample the wetter side of the Highveld Grasslands. Our struggles continued as we faced relentless rain and floods, which saturated the dirt roads we had to take to get to our sites. After getting our bakkie (affectionately named Mole) stuck, for the fifth time we might add, we left it behind and wandered in the dark nature reserves looking for cell service to call for assistance, worrying that we would have to walk all the way back to our accommodation.

Our fieldwork challenges didn’t stop there. We also encountered massive thunderstorms, buffalo circling our plots, hungry cows mistaking us for food bearers, and ostriches guarding their eggs. Despite these hurdles, after two months, we collected comprehensive data: 240 soil samples, 800 biomass samples, and thorough floristic data for 1000 1m² plots, documenting around 500 different species. The lab work and data processing took several months, but we aimed to verify any trends and significance.

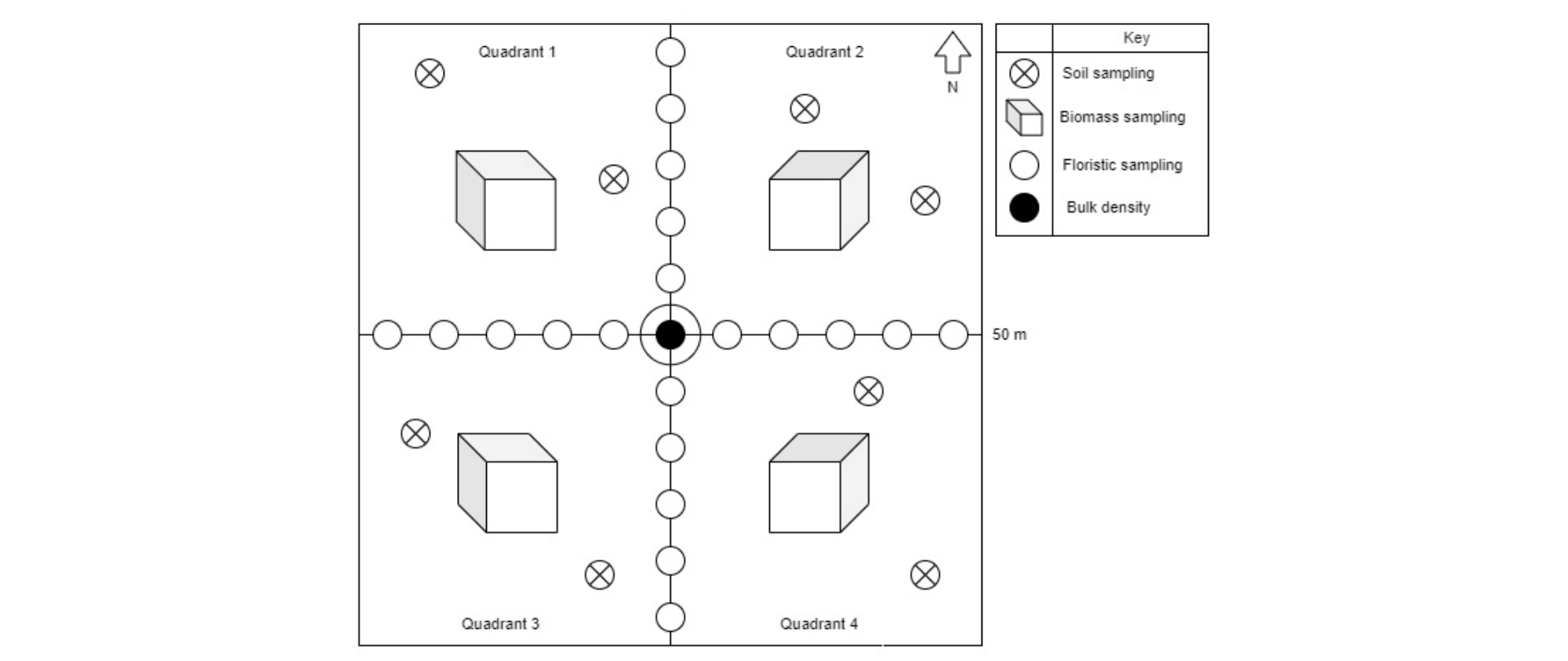

Below is a schematic illustrating the specific sampling protocol we used (Figure 1), which combines the Global Grassy Group ‘Manisa bozaka’ protocol, adapted to include soil studies and biomass measurements for calculating organic carbon stock from both soil and biomass in the plots.

Figure 1: A schematic of the sampling design that Elaine and Eulalia used for their fieldwork. The big 50m x 50m is the size of each plot as laid out in the GGG protocol. The cubes represent 0.5m x 0.5m where aboveground biomass, litter, belowground coarse roots, and belowground fine roots were samples. The x’d circles represent the soil samples that were taken and the black centre circle represents where the bulk density was collected. The 21 unfilled circles represent the 1m2 circular plots that were used for floristic sampling.

Through the use of this protocol we aimed to quantify the loss of floristic and functional diversity between the previously ploughed lands and the old-growth grasslands. It is quite obvious that if you plough land, diversity will be lost – our job was to do what all eager scientists aim to do, prove it.

Each day, we set out in our trusty steed Mole to one of our paired sites for a full day of digging in the dirt and paging through field guides to identify the myriad of plants in the field. Our field observations revealed a disparity in species richness between previously ploughed and unploughed ‘old-growth grasslands’. We noted that management styles influence this disparity. Additionally, the type of surrounding grassland affects species richness recovery; natural reintroduction is higher near old-growth grasslands compared to sites surrounded by farms. This is confirmed by the return of geophytes such as Gladiolus spp., Watsonia spp., and even a few orchid species. While the return of these species is not impossible, it is less likely without external intervention or a natural source area.

We also observed differences in root density based on management styles. Sites grazed almost daily had sparse, thick roots, whereas old-growth grasslands had a dense carpet of fine roots in the top 10 cm and thicker roots extending deeper. These are just some of the observations we made using the ‘Manisa bozaka’ protocol. Despite the labor-intensive field and lab work, our results look promising. We hope our findings will demonstrate the impact of ploughing on grasslands and inspire further studies on other ecosystem factors, such as insect diversity, bird diversity, microbial differences in the soil, and other exciting aspects of grassland ecology.