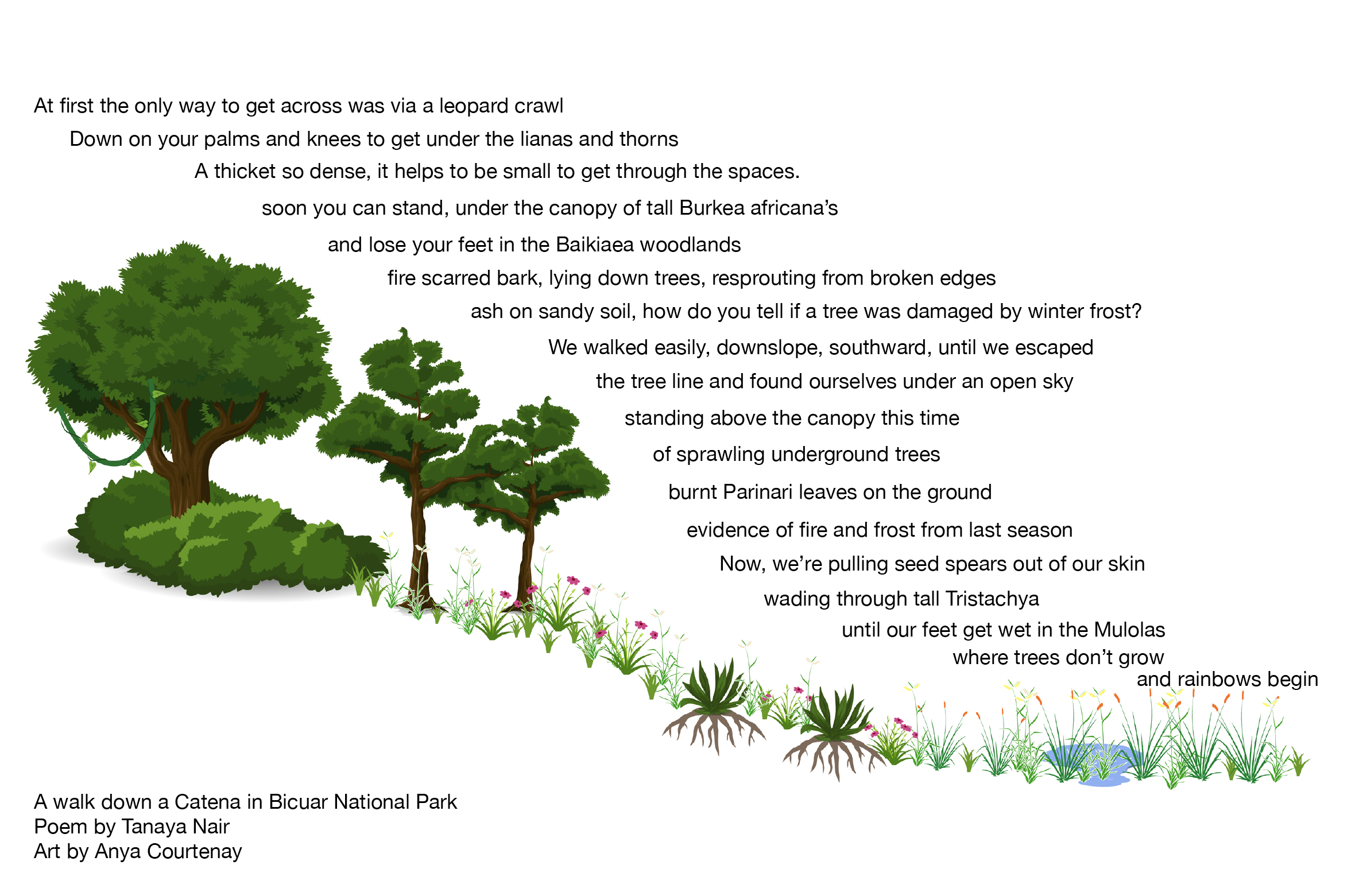

The landscape of Bicuar National Park in southwest Angola is characterised by networks of shallow valleys with slopes called catenas. Up on the crest, locally known as ‘tundas’, are miombo woodlands with open canopies and a continuous grassy understory. In some cases, closed-canopy thickets with dense understories occur. Downslope, you find suffrutex grasslands dominated by geoxyles or ‘underground trees’, which are plants with extensive woody underground storage organs. In the valley bottoms there are seasonally waterlogged grasslands called ‘mulolas’. Work by Teixeira (see Huntly, 2019) initially categorised these different vegetation groups.

Across Bicuar, the SEOSAW network has set up permanent plots to monitor dynamics in the miombo overstory such as growth and mortality rates of trees and smaller woody stems. In February 2024, we were invited to join a collaborative field expedition and sample different components of the understory vegetation and environment. Our team, from Instituto Superior Politécnico Tundavala (Angola), the University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa), and the University of Edinburgh & Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (UK), focussed on two outcomes:

-

To sample herbaceous vegetation on the same plots using the Global Grassy Group protocol to demonstrate ground-layer diversity and how this may differ in response to environmental dynamics in different parts of the catena.

-

To establish microclimate transects across the catena gradient of vegetation types to calibrate microclimate models, with the aim to predict seasonal frost occurrence as a response to vegetation and tree cover.

As we traversed transects collecting our plant and microclimate data, we noticed that some sites across the catena had very stark boundaries in vegetation and others had wider transition zones. It made us ask how and why it is useful to divide these vegetation types into neatly defined boxes and at what scales these distinctions make sense. In this blog, we would like to share field observations and reflect on the nature of each vegetation type, by inviting you to come sampling with us down the catena slope.

Thicket

Starting in thickets up on the catena crests, we weaved ourselves and our tape measures under and over thorny trees and tangled lianas. The visibility was poor in the dense vegetation so we used our voices and GPS devices to navigate through. Although the shade provided welcome relief, we must admit that some of us were reminded why we love working in open, expansive grassy ecosystems! Collecting data here was time- and energy-intensive, but it was valuable to become well acquainted with an ‘alternative’ vegetation state that occurs in the absence of many disturbances.

Miombo

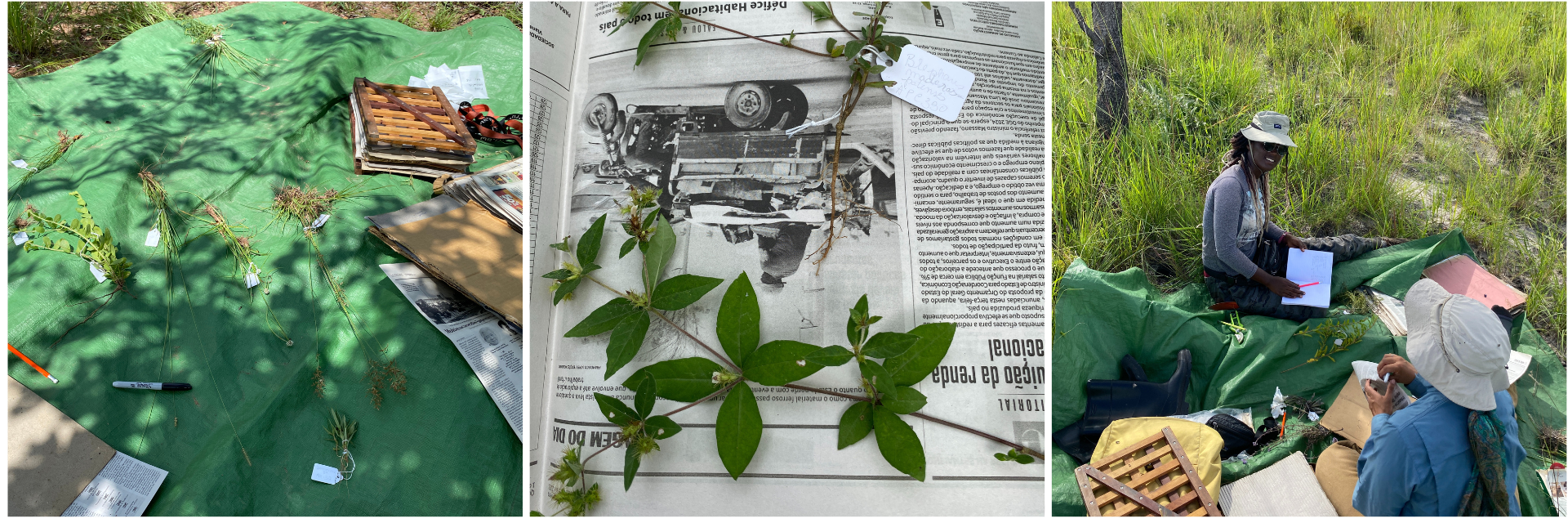

Stepping into the more open canopy of miombo woodlands, a dominant vegetation type in Bicuar and across southern Africa, trees like Brachystegia, Julbernardia, and Isoberlinia tower over you and a diverse ground layer of grasses, sedges, forbs and geoxyles. Where Baikiaea trees comprise the overstorey instead, legumes carpet the ground - perhaps due to a difference in soil properties. Although the same broad vegetation type, each of the 14 miombo sites we sampled had its own feel. Some had denser vegetation, and others were more patchy allowing sunlight to beam through. For microclimate measurements, we took photographs of the tree canopy using a hemispherical lens to measure how much light from the sun reaches the ground. Lacking a tripod, we resorted to placing the camera on a wooden slab over our heads until we heard the image click.

Although elephants migrate to a different part of Bicuar at this time of year, their presence in the miombo could not go unnoticed through the number of trees taken down by their trunks. On the trunks of trees, we found clues to the time since the fire and in our subplots we recorded if there was ash on the ground. The white soils of Kalahari sand provided an ideal backdrop for the 100s of photos we took of the colourful flowers in bloom. We were greeted by butterflies and slightly less welcomed by bees. Termite mounds were always a nice symbol of teamwork as we each found our niche among the sampling activities.

At the edge of the miombo, you reach what has been described as an inverted tree line, whereby the trees are on the top of the slope in contrast to what is seen in other areas where trees inhabit valley bottoms and ravines, such as in South Africa’s Drakensberg mountains, the Madagascan highlands and the shola-grassland mosaics in the Nilgiri biosphere in India. The rolling slopes in Bicuar, however, are at a lower elevation and much gentler than these landscapes. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the lower treelines in Bicuar may be controlled by frost and the cold air that pools in the waterlogged bottom of the catena and restricts tree growth, contributing to the formation of an exemplary woodland-grassland mosaic.

Suffrutex grasslands

To see a tree canopy outside the miombo, you should look down to the ground rather than up to the sky! In the suffrutex grasslands, geoxyles form ‘underground forests’ of large sprawling woody rhizomes and low-growing shoots that resprout between multiple disturbances such as fire and frost. Suffrutex grasslands could be a ‘transitional’ vegetation type between the miombo and mulola, but it has its fair share of unique species and by now we were masters of pressing plants to build up a herbarium collection so that we can confirm identifications of each plant.

We set up three new herbaceous plots in suffrutex grasslands to capture nuance in ground-layer composition, as well as three transects to measure microclimates across vegetation transitions. Having experimented with multiple data loggers, poles and paper cups, our loggers had to be secure enough to last half a year until the frost season but also conspicuous enough not to grab the attention of curious animals. Results from the microclimate transects might indicate the extent to which frost and waterlogging influence the vegetation structure across the catena.

Mulola grasslands

Down in the flatter catena bottom are the mulola grasslands where you can get lost among grass that is taller than you. Topography determines how water collects in a landscape, and the open-ended mulola channels differ from bowl-like ‘chanas’ where rainfall accumulates (often a source of confusion as well as water). Although we could sometimes trace elephant paths, the waterproofing on our shoes would be put to the test crossing waterlogged patches to get to the other side. It was always worthwhile to look out to the landscape from the mulola, seeing vegetation transitions beautifully mirrored on either side of the catena and often under rainbows.

Back at camp

After a long day out, it was a treat to share fresh lemonade, foraged mushrooms and experiences among the groups collecting different datasets. On the final evening we gathered around a bonfire with our wonderful team, a mix of Portuguese and English speakers including researchers, rangers, and field station managers. We shared our interests and projects at Bicuar, recognised common goals and emphasised the importance of regular collaboration.

Some words from Ruth

‘Foi muito interessante utilizar uma nova abordagem de recolha de dados sobre a vegetação e grupos funcionais, uma vez que para o Bicuar em particular, tem-se dado muita atenção às árvores. Incluir outras formas de vida existentes (gramíneas e herbáceas) vai ajudar-nos a compreender melhor a relação entre elas bem como todos os factores implicados na sua distribuição pelos diferentes habitats existentes no Parque.

Para mim, o trabalho também serviu para melhorar e aumentar o meu interesse em taxonomia e gerenciamento de espécimes, caracterização morfológica e funcional das espécies, níveis de endemismo, suas áreas e padrões de distribuição, tamanho da população, condições de habitat e pressões antrópicas, esses dados serão úteis, por exemplo, para a sua avaliação segundo os critérios da IUCN e do estado de conservação em Angola.

O meu muito obrigada a todos, foi uma experiência incrível.’

‘It was very interesting to use a new approach to collecting data on vegetation and functional groups since, for Bicuar in particular, a lot of attention has been paid to trees. Including other life forms (grasses and herbaceous plants) will help us to better understand the relationship between them as well as all the factors involved in their distribution across the different habitats in the park.

For me, the work also served to improve and increase my interest in taxonomy and specimen management, morphological and functional characterization of species, levels of endemism, their areas and distribution patterns, population size, habitat conditions and anthropogenic pressures. This data will be useful, for example, for its assessment according to IUCN criteria and the conservation status in Angola.

Thank you all very much, it was an incredible experience.’

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyle Dexter and John Godlee from the University of Edinburgh, Fernanda Lages at Instituto Superior Politécnico Tundavala (ISPT) and all collaborators at Instituto Superior de Ciências da Educação de Luanda (ISCED) for support in organizing the fieldwork, which was funded through NERC. Huge thanks also go to all who collected data alongside us: Sally Archibald, Justice Muvengwi, Ruth Fransico, Telmo António, Grece Nacale and João Cornélio Vandrekel.